As I wrote recently for Thrive Global, there’s a reason stories have such power — why they’ve resonated since the dawn of time, and why they continue to resonate even in today’s business world, resulting in more engaged listeners and, ultimately, a better ROI.

There are scientific reasons for this, as was once explained by neuroeconomist Paul J. Zak: Stories stimulate our brains to release oxytocin, the so-called “love hormone.” That in turn evokes trust and empathy, and provokes action — up to and including the desire to purchase a product.

As Zak explained to Park Howell on Howell’s podcast “The Business of Story”:

“When we tell stories, we do want people to empathize with us, or with the characters in the story, and that makes us care about them — care about what happens in the story, how the story resolves. We are persuading people.”

Well before Zak began his studies on this topic, psychologist Jerome Bruner wrote in his 1987 book “Actual Minds, Possible Worlds” that listeners are 22 times more likely to recall a story than data. Another study, in 2015, showed that 55 percent of consumers will buy from a brand that relates a compelling tale. That has given rise to the adage that “facts tell, but stories sell.”

I offered several examples of this in the Thrive Global piece, starting with the many tech giants who say that their origins can be traced to a garage. Apple, Amazon, Google, Disney and Microsoft all make that claim, and understandably so. It’s so much easier for a consumer to relate to these corporate monoliths when they are depicted as spunky upstarts, and makes those same consumers much more inclined to buy from them.

So never mind that the tales might be tall ones; Apple’s origin story, for instance, was long ago debunked by Steve Wozniak, who founded the company in 1976 with the late Steve Jobs. The fact is, these stories resonate with customers, build a bond, build a brand.

I cited two more examples of the power of storytelling in the piece, including another featuring Jobs himself. When he introduced the first iPhone during a presentation to company employees in 2007, he started out by showing a photo of Apple’s first desktop computer, which came out in 1984 and in his words “changed the whole computer industry.”

Then a photo of the iPod was displayed. When it was released in 2001, he said, it “changed the music industry.” And finally he announced that Apple was poised to release “three revolutionary products” — a widescreen iPod with touch controls, a mobile phone and “a breakthrough Internet communications device.”

Three products in one, he added quickly. And in doing so, he said, “Apple is going to reinvent the phone.”

His employees, duly impressed, cheered. (That, in and of itself, reveals one of the positive side effects of a good story: It engages not just consumers, but a company’s own workforce as well. Howell, on his podcast, also mentioned potential benefits being career advancement, business leadership, content marketing and sustainability, emphasizing that everyone is “hardwired for story.”)

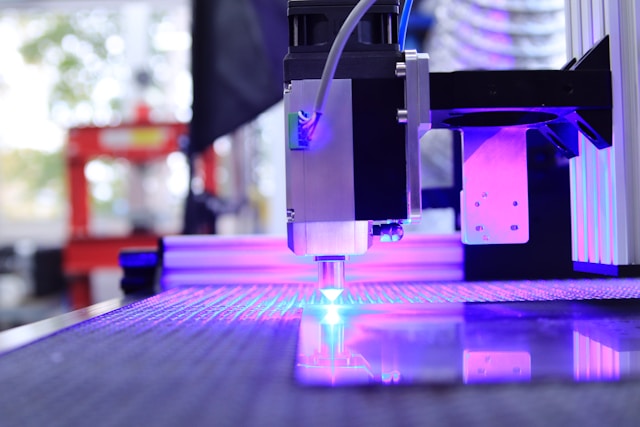

One more example I mentioned in the Thrive Global piece is that of a six-minute, 22-second B2B ad Hewlett-Packard circulated in 2006 for its secure printer. It stars actor Christian Slater, and demonstrates just how easily a cybercriminal could infiltrate a business through a printer that is not secure.

The ad is really well done, and relates a powerful story. But as we’ve been reminded again and again over the course of history, stories are like that. They rattle around in our brains, illuminate our thoughts and stimulate action. There’s truly nothing quite like them.